Snail and ancient history conservation come head-to-head in Bagnor

The photo above shows an aerial view of the planned conservation works at Bagnor on the River Lambourn. with an inset showing a Desmoulin Whorl snail.

Conservation work is being carried out on a stretch of the River Lambourn on the Bagnor Estate in West Berkshire.

And a small, little known creature is at the heart of it.

This floodplain site contains wet woodland and fen swamp habitat, designated for the international importance of the Desmoulin Whorl Snail population.

So work is underway to create further wetland habitat on site to help maximise the populations of this species, and the connectivity of habitats it depends on in the Lambourn Valley.

But this seemingly worthwhile venture might hit a blocker – because of an old piece of wood, and some ancient history.

The district archeologists have also been asked for views on the proposed works.

They say these groundworks have the potential to have an impact on heritage assets of archaeological interest.

“Within this 2km stretch of the river are several known historic environment features as well as potential deposits,” explains Sarah Orr, senior archaeologist.

“The site itself contains post-medieval water meadows so their channels and structures might be affected, but of greater national significance is the fact that the river valley may contain peat with palaeoenvironmental evidence.”

She says the importance of the Kennet Valley for early prehistoric archaeology is well known, but it now appears that the Lambourn Valley may also have high potential.

Just 1km upstream of the north end of this proposal site, a large piece of waterlogged wood was recovered from within peat, in a similar position on land next to the Boxford water meadows.

“This was recently in the national news as Britain’s oldest known carved timber, radiocarbon dated to around 4640 to 4605 BC,” she explains.

“We are now exploring with Historic England what the implications are for this exciting discovery. Additionally, 100m away from the site on the sides of Hoar Hill is a large Roman villa complex, partially excavated in 2012-15.”

She says the Lambourn would clearly have been utilised during the Romano-British period, most likely at a point where the bank was closest to the buildings.

There is also the suggestion that there was a second Boxford water mill, perhaps near Moor Bridge.

So before the conservation for the snails’ habitat begins, she wants to know what the Environment Agency’s own procedures are for screening their proposals against possible adverse archaeological impact.

“I am concerned that in the desire to deliver ecological improvements to the SSSI and SAC, fragile archaeological deposits or artefacts may be heedlessly lost.”

The estate is working with the Environment Agency to preserve the natural functions of the chalk river system and had applied for an unusual planning permission from West Berkshire Council to carry it out.

It has applied to restore river habitat using a variety of techniques including re-profiling river banks, restoration of river bed gravels using gravels excavated from the floodplain, and use of woody material to create in-stream diversity.

Conservationists also plan to excavate floodplain areas, to encourage areas of open water – a network of shallow scrapes and seasonal and permanent open water habitats – with the objective of increasing species diversity.

The River Lambourn is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Special Area of Conservation (SAC).

It is a chalk river of international importance.

The Environment Agency says that despite its designated status and international value, the river is still failing to achieve what it describes as its “ecological condition objectives”.

One of the principal reasons for this failure is due to historic modifications made to the channel for flood risk, land drainage and landscape purposes.

The Environment Agency along with Natural England and many individual landowners have been working to deliver a strategy to secure long term ecological improvements on the river.

Projects already delivered include river restoration, wetland reconnection, removal of in-channel structures (weirs, sluices etc), and the creation of fish passes.

The long term aim is to create a naturally functioning chalk river system, whose natural processes help create and sustain diverse in-stream habitats.

This would allow unimpeded movement of species throughout the entire length of the river; and to restore floodplain connection – providing functioning and thriving wetlands for the benefit of biodiversity, flood risk, and carbon and nutrient budgets.

At Bagnor Estate, on the river Lambourn, the landowner is also keen for the site to be used as an educational resource by schools and community groups in the area.

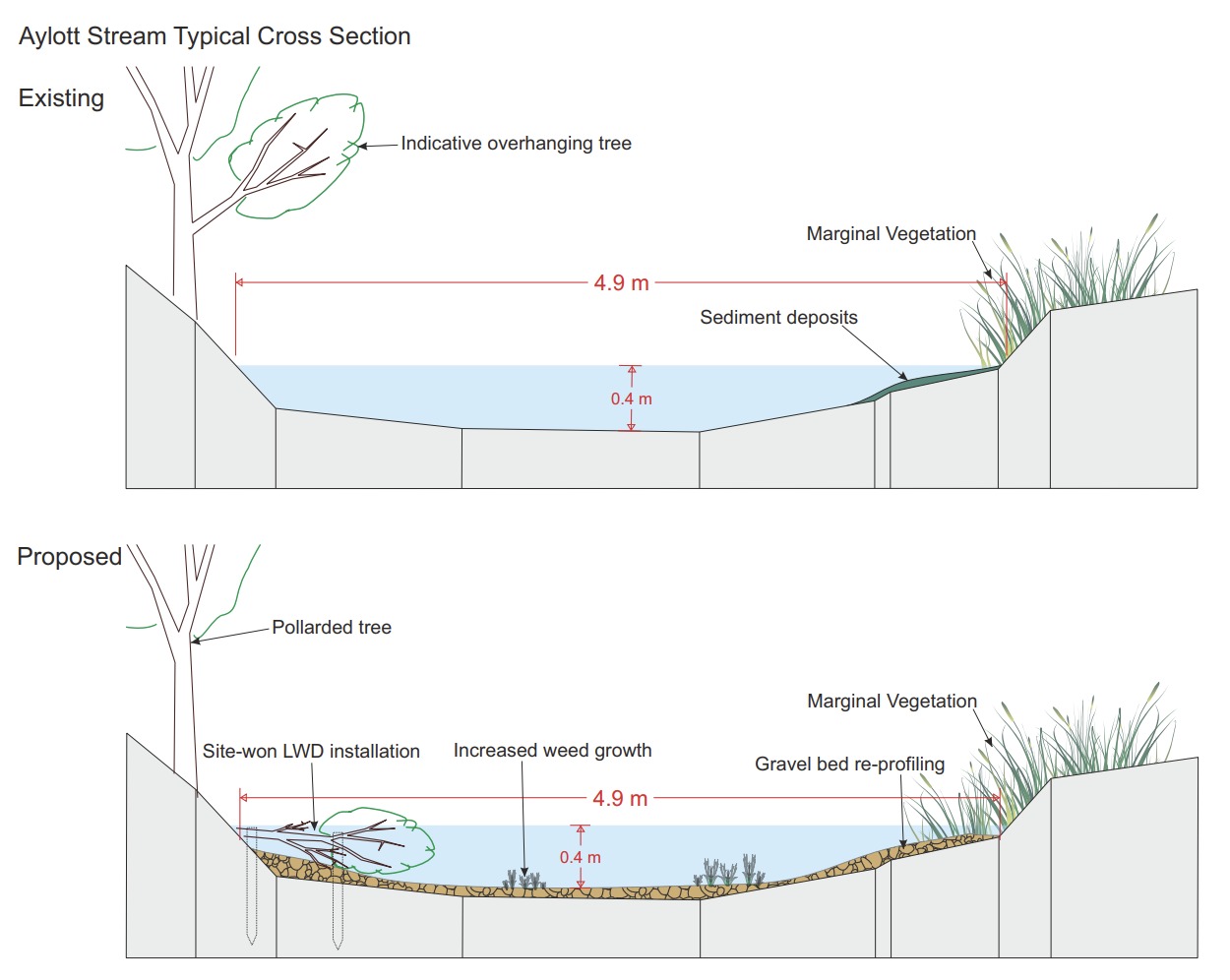

Parts of the River Lambourn on Bagnor Estate have been restored – taking a previously over wide and deep channel, and restoring a more natural cross section and habitat diversity.

In addition, two historic weirs have been removed, restoring natural river process and connectivity through the reach.

This project extends the length of river restored, including that of the Aylotts Stream, a SSSI distributary from the main river.

As well as the river restoration, the project will deliver creation of wetland habitats, and floodplain connectivity.

The project has been proposed and designed as a partnership between the Environment Agency, Natural England and Bagnor Estate.

Funding is secured from a partnership between Bagnor Estate and the Environment Agency.

The decision on whether the works go ahead now sits with West Berkshire Council.

The graphic below outlines the proposed works at Bagnor on the River Lambourn