How a humble snail held up the Newbury by-pass

(Photo above: Vertigo Desmoulinsiana)

Along with rare bats and certain types of newts, another small but, shall we say, influential creature has a say on planning permissions in West Berkshire.

The diminutive Desmoulin’s whorl snail has a consistent presence in the red tape.

Known as Vertigo Moulinsiana, it is one of 11 types of whorl snail found in the UK and Ireland. They are typically smaller than a baby’s fingernail with a shell height up to 2.6 mm.

Bat tunnels costing over a £100m on the HS2 project hit the headlines recently.

Great Crested Newts have significant pedigree in stopping planning applications.

But Newbury can claim its place too – the rare snail almost halted the construction of the controversial Newbury bypass decades ago, with the government at the time also forced into a conservation corner, paying £250k to move the snails away from the path of the bypass and creating a 100 metre tunnel to divert water from the Kennet for them.

Proposed by the Department of Transport in 1984, the Newbury bypass was a controversial scheme which faced fierce opposition from some local residents and environmentalists.

The route ran through sites of significant scientific and historic interest and it was discovered that areas affected in the Lambourn Valley were home to a rare miniature snail, known as the Desmoulin’s whorl snail.

Nonetheless supporters argued that the road scheme was the most cost effective and environmentally friendly proposal to alleviate traffic congestion in Newbury.

The bypass was debated for many years with two lengthy public inquiries in 1988 and 1992.

In June 1996, a coalition of environmental groups applied to the High Court to halt construction of the bypass in order to protect the snail.

Dr Susan Millington, coordinator of Newbury Friends of the Earth, who was one of the campaigners against the Newbury bypass said: “One of the country’s major colonies of the rare and internationally protected Desmoulin’s whorl snail was discovered on the route of the Newbury Bypass in early 1996.

“We protestors were jubilant when construction was halted (alas, only for several months) while the Government was taken to court in an attempt to protect the endangered snail and its habitat.

“The case failed on a technicality, but the High Court Judge, Mr Justice Sedley, noted that ‘if the protection of the environment keeps coming second we shall end up by destroying our own environment’.”

Having received permission to go ahead, the Highways Agency then began the painstaking process of attempting to relocate the snails to a new home.

Under the guidance of English Nature, large sections of earth containing reeds and sedges were moved to form a habitat of 3,200 sq metres in the Lambourn and Kennet Valleys.

Having seemingly resolved the issue, in August 1996 construction work commenced and the road opened to traffic in 1998.

In 2006 it was widely reported that despite the efforts to save the molluscs, the snails had sadly died out in the area that they had been moved to – although this seems to still be a contested point.

The effort that the Department of Transport went to in order to both build the bypass and save the snail led to the small creature becoming somewhat of a mascot for the road scheme.

Campaigners even mowed an image of a giant snail on a local hill as part of their high-profile protest.

But the humble mollusc may yet have a part to play in development plans for West Berkshire.

West Berkshire Council still has a special planning category for protecting it (and other species on the list) called a Habitats Regulations Assessment, which is part of the planning process.

An HRA is required to assess the potential effects of a plan against the conservation objectives of any European sites designated for their importance to nature conservation.

Within West Berkshire there are three designated sites.

As you might expect, buried deep in the chambers of parchment rolls that is the West Berkshire Council archive, there are weighty documents which explain all of this.

Although the latest one, marked December 2023, makes note that the UK is no longer in Europe – but a moot point, perhaps.

The regulations ensure that the habitat and species protection and standards derived from EU law will continue to apply after Brexit.

Where previously sites were referred to as European or Natura 2000, the sites now make up the UK ‘national site network’.

Still with me?

The Desmoulin’s whorl snail requires permanently wet, usually calcareous, swamps, fens and marshes, boarding river, lakes and ponds, or in river floodplains.

If water hungry developments are located close to where it lives/could live, there is a risk that the requirement for large amount of water could lead to drying of the floodplain – and the snails.

But there are exceptions to the rule, as an assessment of ‘imperative reasons of overriding public interest’ can be done.

And if it is deemed so, the plan should proceed. This is not a standard part of the process and will only be carried out in exceptional circumstances.

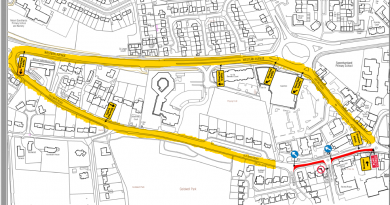

So any applications in the Kennet and Lambourn Floodplain get tripped up by the snail unless a good plan to not change the habitat is submitted.

Which brings us to the hefty amount of housing development planned for West Berkshire.

Development within West Berkshire over the local plan period will increase wastewater production and add pressure to the existing sewerage systems.

Run-off, outflow from sewage treatments and overflow from septic tanks can result in increased nutrient loads and contamination of water courses.

There are 30 wastewater treatments works relevant to West Berkshire covering six catchments, which are expected to see an increase in effluent as a result of growth within their catchment.

There are no Habitats Sites within the Upper Kennet and River Enborne catchments, nor the Pang catchment, so there is likely – according to the council documents – to be no impact from the proposed development.

Which seems a bit contrary bearing in mind the hoo haa going on with water companies pumping dear knows what into the rivers.

“This pattern of the natural world coming second has continued to this day, and now we are confronted with the blatant attack on nature which is the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, at present in the House of Lords,” added Dr Millington.

Obviously there is a right ding dong going on about Thames Water and its current and apparent inability to keep sewage out of chalk streams – including the Kennet and the Pang – and the home of the would be Desmoulin’s snail.

Thames Water has faced mounting criticism for repeated sewage spills, including in the River Kennet and Lambourn streams, and for failing to invest adequately in infrastructure while burdened with billions in debt.

Newbury MP Lee Dillon said: “The people of West Berkshire are fed up with sewage in our rivers, excuses from Thames Water, and inaction from the Government.

“It’s time to blow the final whistle, put this failing company into special administration, and focus on protecting our environment.

“Special administration would mean its debt can be written down and real investment made in stopping sewage discharges.

“Alongside this, we urgently need a new, capable water regulator with the power to hold companies to account.”

But it doesn’t appear they need planning permission to pump out sewage, nor does there appear to be any meaningful enforcement to stop them doing it because it upsets the snails.

The council has commissioned a Water Cycle Study which states that upgrades to sewage treatment works and waste water networks will be required to meet the needs of population growth during the local plan period (up to 2039).

Development can create so-called ‘edge effects’ from housing and domestic activity potentially including disturbance and erosion from cycling, trampling, littering, dog walking, cats, fly-tipping and the introduction of non-native invasive species.

Where development is likely to result in an increase in the local population, the potential for an increase in visitor numbers and the associated impacts at sensitive sites need to be considered, it says.

Crunch. Skid.

But there is hope for our snail. And anyone planning a protest against more development.

Suspicious colonies of the Great Crested Newt have turned up at development sites across the UK, according to a Conservative member of the House of Lords.

During a debate about affordable housing, Conservative peer Lord Borwick claimed that the newts were planted by development opponents in order to halt construction. The newts are a protected species under UK and European law – much like our snail.

But creating a mass population of Desmoulin’s for placing strategically around planned sites for big housing developments in West Berkshire might take more than popping a handful of snails in the boggy, weedy bit of the garden in the hope that nature can take its course to produce a vast population of the little fellas for sprinkling around Thatcham.

Apart from anything else, that would be naughty, wouldn’t it?

The potential building of 2,500 houses on the edge of Thatcham at an average occupancy of 2.4 people per household equates to an extra 3,600 people.

The Ramblers Association participation rate indicates a potential demand for 1,320 walks every four weeks or 47 walks per day.

Not all of these will occur on or in the vicinity of our snail’s home – and new residents closer to the sensitive sites may choose other rights of way and available open space closer to their residencies.

And our snails can count on humans being, well, lazy.

Ramblers evidence shows that access on foot declines significantly beyond 500 metres. We prefer the car.

Due to many years of urban and agricultural activities, many protected areas are already fragments of habitat that have not been developed upon. Yet.

Further development may have the effect of causing further fragmentation or damage of habitats and/or severance or blocking of ecological corridors between linked sites, according to the council’s own paperwork.

Loss of habitat from outside the boundaries of a site could also affect the integrity of that site if the habitat is used by the qualifying species from the site for off-site breeding, foraging or roosting.

The sites that have mobile species among their ‘qualifying’ features include our friend the Desmoulins’s whorl snail and the Thames Basin Heaths, which have Nightjar, Woodlark and Dartford Warbler.

The cluster of sites selected in the Kennet and Lambourn valleys support one of the most extensive known populations of Desmoulin’s whorl snail in the UK.

And the policy goes that the conservation objective related to the sites’ designation is to ‘maintain in favourable condition, the habitat for the population of Desmoulin’s whorl snail.’

What decision-makers typically look for to tick off a planning application is something called hydrology management – that the plans before them demonstrate no adverse change to water levels or quality supporting habitats that the snail relies on.

Meanwhile the critters fight on.

The Great Crested Newt is a little further down the line with its survival PR than our snail right now. There is an organisation called Froglife which looks to its interests.

Froglife recently said it was ‘disheartened’ to hear MP Angela Rayner’s comments that, “newts can’t be more protected than people who need housing” and this continued rhetoric in Rachel Reeves’ recent speech on planning reform where she singled out newts as the cause for planning delays.

In 2020, Boris Johnson, then Conservative prime minister, said “newt-counting delays” were a “massive drag on the prosperity of this country”.

And there are numerous other examples where great crested newts in particular – have been portrayed as the reason that millions of homes haven’t yet been built.

It seems the housing and nature agendas are pitched against each other.

The current government has made promises to build more houses, AND protect nature – but the newt is clearly taking the heat.

Therefore, would it be in their best interest to work with environmental NGOs to do just that in order to achieve their targets?

It all seems a bit pointless though, all the paperwork and legal protections in place to help the snail live its best life.

Water companies spilled raw sewage into England’s rivers and seas for a record 3.6 million hours in 2024, according to Environment Agency figures.

Now. I have a nice soggy patch at the end of the garden…where is that bucket of snails?